EXPERT WEBINAR SERIES

With CompuMed Expert Dr. Robert Shiroff

FREE On-demand Webinar

Renowned Cardiologist and CompuMed Chief Medical Director, Dr. Robert Shiroff presents a webinar on the unique role of Heart Catheterization in Donor Management. This is both practical and technical, touching on the why and how of improving donor management through heart catheterization.

Topics include:

- Importance of heart cath in overall donor management

- Donor focused interpretation of the procedure for potential heart placement

- Reading and review of heart cath

- Insights on how to increase the number of transplantable hearts

Who is this for?

Donor and Transplant Professionals

KEY TAKEAWAYS:

- Minimum two views of the Right Coronary Artery, Left Anterior Oblique (LAO) and Right Anterior Oblique (RAO).

- Multiple views of the Left Coronary Artery with adequate unlapping of major branch points (left anterior descending and left circumflex arteries).

- Documented pressure measurements, oxygen saturation and cardiac output for Right Heart Catheterization.

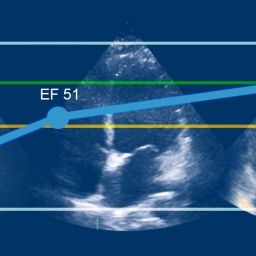

- High quality RAO projection cineangiogram of the left ventricle (adequate for estimated EF%).

Robert "Bob" Shiroff, MD, FACC

CompuMed Chief Medical Director

Clinical Cardiologist

Dr. Shiroff is a board certified cardiologist with a fellowship in clinical pharmacology as well as an experienced medical expert witness.

CompuMed is honored to have Dr. Shiroff on our team as he serves the donor and transplant community. His in-depth knowledge and expertise helps assess, manage, and improve the recovery of donor hearts, resulting in an increase in the number transplanted into needy recipients. Knowing that each recovered heart has the opportunity to save a life is humbling and extremely rewarding. We are grateful for his passion to share his knowledge and experience with the OPO and Transplant community.